Where Magic Is Bought By Maskelyne

Boxes of simple tricks—New tricks—Magic and carpentry—‘

Magic thread’—Making friends—Getting the

right costumes—Apparatus for ‘escapes.’

Where is magical apparatus purchased?

This is a very big and very important question, and I think I should answer it as soon as possible. In the first place, the simple tricks are obtainable at any large store in London, and you will learn by experience which shops are best for Chinese rings, prepared cards, paper-tricks, and so forth. Hamley’s, in Regent Street, London, and Gamage’s, in Holborn, are very good firms for magical apparatus. The young magician who is just starting to get a show together will have to look round for a shop selling appliances where he can become known as a good and valued customer. In this magic-business there is nothing like making a friend of the man who sells you your apparatus, because he will then be on the look-out for new tricks as they come on to the market, and will let you know immediately they are available.

Do not at first scorn the boxes of simple tricks sold at most large stores in London and the big provincial centres. Admittedly they may contain a few tricks that are really too well known to engage your professional attention; but on the other hand these boxes will give you a basis for your show. Many a fresh idea has come to me through seeing a sixpenny wiretrick. It is something like starting a course of construction with a Meccano set; you have got to start at the beginning and gradually work your way up.

I would therefore strongly advise those of you who are making an early start in magic to buy a large box of conjuring-tricks—you may be able to obtain a big box second-hand from an amateur conjurer—and then slowly build up your collection of tricks by buying single items as you find good ones. Every day new tricks are being placed on the market, and the successful young magician must use his eyes if he is to keep ahead of his rivals. He must make a point of visiting his favourite magic-shop once a week and having a good look round. In addition, he must bear in mind that one really first class trick which takes a little time to present is often better than half a dozen mediocre tricks that a child could perform with success.

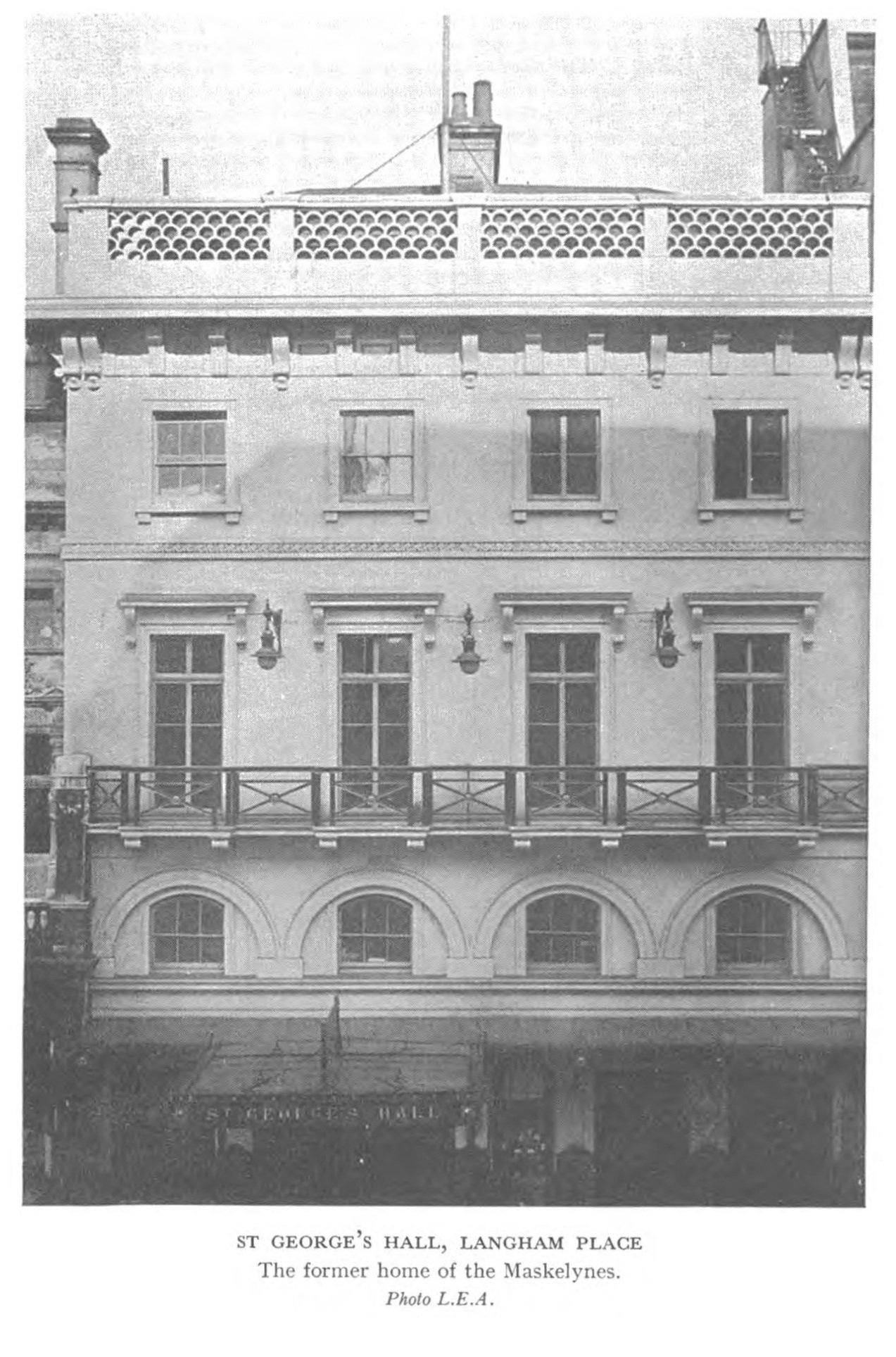

All the big magicians have their own particular magic-agents, and they are constantly on the alert for brand-new tricks or modifications of old ones. Now for a big secret—I use an agent named P. T. Selbit, a great magician. I use him because he is the best man I know, and also because he employs one of my best ex-carpenters in his workshops. In the days when Maskelyne’s performed at St George’s Hall, London, we had our own workshops underneath the stage, and it was here that many of the most baffling of the Maskelyne illusions were constructed by this man and other expert carpenters. As you progress with your magic you will discover that the actual making of illusions is an art in itself, a specialized business in which there is no room for failure. You must have things right to the smallest fraction of an inch, or the whole trick will fail. You must spend hours and hours in patient research, like a chemist, and you must use the best material and the finest tools. In that workshop beneath St George’s Hall we kept secrets that other magicians would have given their ears to learn; but every single piece of apparatus was removed, to leave nothing more than the floor-space, when the British Broadcasting Corporation took over the hall. In the past I have spent many hours in that workshop with my assistants and carpenters, and some of my greatest professional thrills have been experienced in that secret room behind locked doors. I recall the discovery in the early hours of the morning of a method of making a certain cabinet, and I remember how I danced in and out of the littered apparatus in my excitement. My grandfather, the first Maskelyne, not only used the workshop attached to the hall in which he gave his shows, but also had another in his house. Often he did not go to bed for nights on end when in the midst of building an illusion.

I must confess that I am a trifle sad when I think of that deserted cellar of wonderful memories under St George’s Hall. However, times must change, and I must change with them. P. T. Selbit is a positive wizard when it comes to making tricks and illusions. He can construct anything from a disappearing-box trick to a headless ghost. Quite recently he has made me a box-trick for the sum of £10 which I have performed with great success. The price of the bigger illusions varies according to the amount of work put into it, and I find it best to work out my illusions on paper first and then get my pet carpenter to work out a figure. It was Selbit who originated the ‘sawing a woman in half’ illusion, although other magicians and expert ‘magic’ carpenters have since improved upon it. That is the whole point of this strange business of ours—it doesn’t matter how perfect an illusion may appear, it can usually be improved upon by enlisting the aid of a carpenter who knows his job inside out and backward.

As a matter of fact, I would suggest quite seriously that, if you find you are not cut out for the actual performance of tricks, if you find that your hands are not suited to the game, or if you have not the necessary stage-presence, you should try making other people’s tricks instead. Here is a profession that is not over-crowded, something that grips the imagination, and, furthermore, something that is profitable as well as interesting. At all events, I think that young magicians should be handy with tools and start a small workshop where they can make and invent some of their own tricks. It is obvious that a new trick that is invented by the performer must be more successful than any other, because it is as novel and up-to-date as it can be. The late Howard Thurston, the great American magician, and a man I greatly admired, was always inventing tricks of his own. Indeed, one of them, the ‘rising-card’ illusion, made him famous and really launched him upon his successful career. Later on in this book you will find a chapter on Thurston, and when you have read it I am sure you will want to start fitting out your own workshop at once!

A propos of this question of having a workshop of your own, I must add that it is essential to create an atmosphere of mystery and surround it with that atmosphere. Keep the door securely locked and bolted, do not allow strangers to enter, and cover half-completed tricks before you leave the workshop for the night. There is a limit to this secrecy, of course —a limit that poor Lafayette the Great passed, as you will read in the next chapter; but in the main I would say guard your secrets as the vaults of the Bank of England are guarded. If rivals or even members of your audiences happen to see the way you are doing your tricks, you will have to scrap your whole show and start all over again.’

Now we come to a very important part of the magician’s equipment—his ‘magic thread.’ Again and again the failure or success of a trick depends upon this almost invisible thread. It must not be seen by a single person in front of the footlights, it must be just as strong or as weak as the illusion demands, and it must be placed in such a position that it allows for the free movement of the magician and his assistants on the stage or platform. The best place to get this thread I find is at Johnston’s Mills, Scotland. It is not really magic in the sense that it is made in a cave hidden away in the mountains of Scotland, but it is a very thin, very strong, and very special kind of thread. All you have to do is to write to the manufacturers, giving them the particular stresses you need, and samples will come to you almost by return of post. It is then bought in I-lb skeins and used as required. Naturally there are other firms who will supply this thread, but I go to Johnston’s Mills because they have never let me down and because I know them, and they know me! There is the personal touch again, you see—the definite connexion between the magician and the manufacturer.

You will have to learn to tie this thread, to use special knots that will come undone at a light tug if you wish to get rid of the evidence of trickery; but all that will come in time. The great point is that you will need a good supply of ‘ magic thread ’ in the very beginning, so that you can perform apparently miraculous tricks easily and well. Good tissue-paper is another item you will need for your show, and in addition you will have to buy rolls of coloured paper specially packed; special safety-pins, and ordinary pins that have been bent; silk of an amazing thinness and softness; velvet for draping your stage; and other materials which are used by the biggest magicians in the world.

All these things may be procured from the manufacturers when you decide to turn your hobby into something a little more profitable than a mere hobby. Another item, playing-cards, you will find rather an expensive one if you are going to put on any number of card-tricks. It is a strange fact that audiences like to see brand-new, sealed packs of cards used for the tricks performed by card-manipulators. This being so, you will have to keep a goodly supply of unbroken packs by you, and I suggest, therefore, that you have some arrangement with a firm of playing card manufacturers to supply you with so many packs a year. You will find that this will work out much cheaper in the long run than if you buy packs as you need them. In addition, it is possible for you to arrange with the makers of playing-cards to print specially prepared packs for you, as well as individual cards with ‘pips’ on each side and other items of trickery. You can get quite a number of these tricks at shops like Hamley’s and Gamage’s, but when you wish for tricks of your own invention you will have to have them printed to order by publishing-houses. In this connexion I would strongly advise the cultivation of a friendship with a printer. Tell him what you are, and what you want to do; take him into your confidence, and make him as interested in your tricks as you are yourself. Then he will give you all the help he can and be unlikely to give your tricks away.

JASPER MASKELYNE

Before Magic Edition

PDF | 301 Pages

Jasper Maskelyne, the famous illusionist, presents a practical book that enables the curious to become expert entertainers in the art of magic. A guide filled magic effects you can perform with cards, coins, handkerchiefs, pieces of paper, rope and other common objects are described in detail. Chapters are also provided on stage management, thought-reading, disappearing tricks, apparatus, chemical tricks, entertaining in dress-clothes, jugglery and ventriloquism, and the art of make-up.

Coming from the famous Maskelyne family of magicians, Jasper also shares some excellent advice on rehearsing, structuring, writing, and booking a magical performance.

Coming to match-box tricks, cigarette-tricks, eggtricks, and the like, I cannot do better than tell you to trust to your own fingers and your own ingenuity. You must learn to ‘blow’ the contents of an egg so that it has the appearance of a new-laid one and yet is nothing more than an empty shell; you must learn how to make a trick match-box look like any other match-box, and yet be so riddled with gadgets that you can very nearly give a complete performance with it; you must be adept at glueing things together so that it is impossible to detect that they have been glued—even at close quarters; and you must cultivate the art of making paper rings so that they may quickly be inspected by members of your audience without the slightest fear of your handiwork being exposed.

It is all a matter of practice, but coupled with that you must have nimble fingers that do not develop into thumbs when engaged on delicate operations requiring skill and patience. It is easy to tell you where to buy ready-made tricks, and where to get the bigger illusions ‘made to measure’; it is a simple matter to tell you that P. T. Selbit will make you a headless ghost for delivery as promptly as your grocer delivers a pound of cheese; it is easy to go to Scotland for your ‘magic thread’: but I cannot tell you exactly how to make your own private tricks. That is a matter for you, and you alone.

With little strips of wood, with little bits of wire, with a pot of glue, with tiny wood-screws, with paper, and with old cotton-reels, you can make the most baffling tricks in your own workshop.

You will need costumes for your various shows, and you would be wise to go to some good theatrical costumier and have them made for you. Later on I will give you hints upon how to put on a Chinese programme or a wizard show, but in this chapter I will merely remind you of the necessity of having clothes that are perfect in every detail and yet suitable for the tricks you intend to perform. Once again it is necessary to get on friendly terms with the man you choose to dress you. Be frank with him, and he will take a personal interest in you and be as proud of your success as you will be. I know my tailor is proud of my appearance and I know he gets a great deal of satisfaction out of watching his suits stride across the stage. Let the man who dresses you be just as proud and just as eager to help you put your show across the footlights.

Let us now go over what I have said in this very important chapter. In the first place you must go to the big stores for your simple tricks, which are sold in boxes with full instructions. Then you must add to them from time to time by buying single tricks as you discover them. Next you can go to P. T. Selbit, Ellis Stanyon & Co., of West Hampstead, London, or any other maker of magic for your bigger illusions, which include boxes, baskets, cabinets, cages, and frames. You can obtain ‘magic thread’ from Johnston's Mills, Scotland. Lastly, you can make quite a large number of good tricks in your own workshop.

I am assuming that you intend to deal with all branches of the magic art. If you are going to specialize, then you will of course have to keep a sharp look-out for new tricks appertaining to your own particular branch. The specialist can rarely afford to run one programme for very long; he must chop and change much more frequently than the magician who can put on a mixed programme of tricks introducing card, ball, egg, match-box, basket, box, cabinet, coin, paper, and rope. One big point: how can you acquire special apparatus for ‘escapes’? You must go to a reputable locksmith and introduce yourself. Explain to him exactly what you want, and, if possible, get him to tell you how various locks are made, how to take an impression of a key with soap, how to pick a lock with a hair-pin or a piece of ordinary wire, and how to keep a lock well oiled so that it is impossible for it to squeak when in use. Give your work to the same locksmith if you can possibly manage it, and add him to your circle of friends who will be ready to help you perform your illusions at any time. Houdini is said to have worked for a locksmith and thus learnt many of the tricks of the trade, but even if you cannot do this you can at least learn a great deal from an acquaintanceship with a man whose business it is to make locks and keys. There will come a time, if you progress in the magic art, when you will need expert knowledge of locks and keys. Therefore, acquire this knowledge very early in the business.

Obtain some books on the subject, and study them. It is astonishing the number of things a magician must know before he can hope to succeed fully. Nothing is too out-of-the-way for him to mark, learn, and inwardly digest; nothing too obscure for him to delve into and find out the whys and the wherefores; and nothing in the art too big for him to tackle.