Specializing In Magic By Maskelyne

Is specializing wise?

—Great magicians who specialized—

Houdini, Chung Ling Soo, Carl Hertz,

the Great Lafayette, van Hoven, the Zancigs—

A final word on specializing.

Specializing in magic presents one vital problem— the public will grow tired of one’s particular type of entertainment. There have been many successful specialists in magic, as we shall see, but they have always lived in dread of audiences growing weary of their acts and turning to some one else—some one with a new and novel show.

The young magician may find that he is particularly brilliant at escaping from handcuffs, packing-cases, and so forth; he may take more readily to card manipulation than to other branches of the magic art; or he may be witty and find it easier to perform simple tricks with plenty of humorous patter than to stage elaborate illusions requiring time and expense. Whatever line he excels in, there is always the temptation to develop it more than any other and finally to become a specialist. I have no right to say “Don’t specialize,” because I count among my magician friends many clever and successful one-act artistes; but on the other hand I do not propose to recommend it, for to-day more than ever the public is restless, demanding constant change. Even in the days of my grandfather, the first Maskelyne magician, who with Mr Cooke created a world-sensation with their stage-exposures of fraudulent spirit-mediums, it was eventually necessary for them to change their type of act, the public tiring of the original performance.

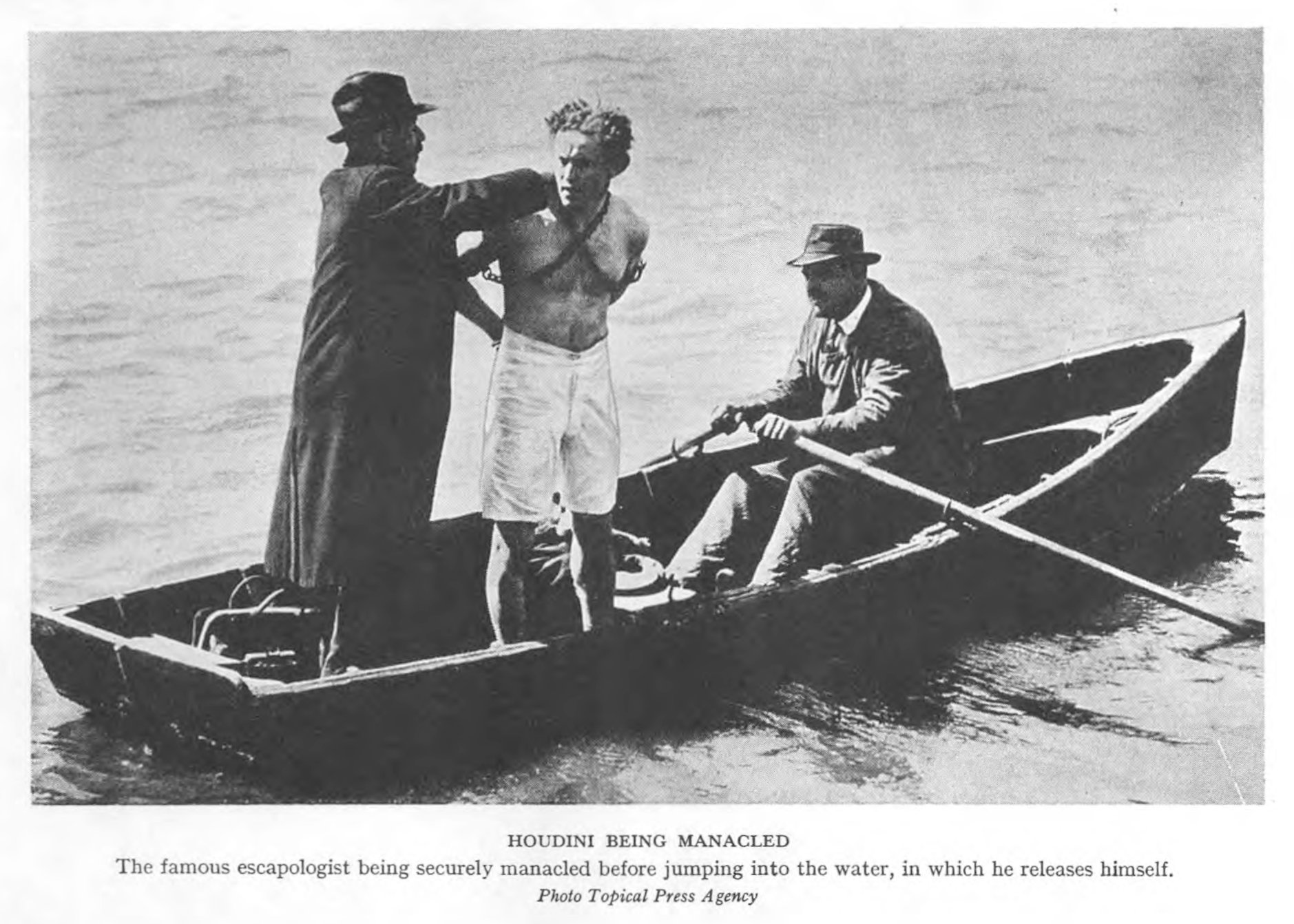

If, however, I tell the story of the more famous specialists, I will consider that I have done my duty by leaving the young magician to decide for himself whether to travel along the one road or to explore the many by-ways. Reviewing the lives of the most brilliant magicians, I think I can say without fear of contradiction that the American Houdini was the greatest escapologist of all time, and that the entertainment-world lost a most versatile artiste when he died at a comparatively early age. The manner of his death was as strange as his life. In his dressing-room at Montreal a student, who had heard it said that Houdini could receive terrific blows to the stomach without ill effect, tested the truth of the statement by delivering several powerful punches. These were the cause of the magician’s death a few days later.

The truth of the matter is that Houdini was not prepared for such blows and so died at the pinnacle of his fame. But we are discussing Houdini in life, not death; one does not write a biography and start with a person’s decease! Let me therefore take you swiftly back along the years to April 6, 1874, when a son was born to a certain Dr Mayer Weiss, a Jewish Rabbi, of Appleton, Wisconsin, U.S.A. The baby was named Ehrich Weiss. At six years of age the boy’s hobby was conjuring, just as it is the hobby of many boys to-day, and the first trick he learned was that of making a dried pea appear in any of three cups. He was an acrobat as well as a conjurer, and as he had a fine body he became interested in releasing himself from ropes and chains, and in picking up pins with his eyelids. So clever was he at this that at the age of nine he obtained an engagement with a circus visiting his home town.

The boy’s father now took action. He would not permit his son to go off with the circus. It was a misfortune for the lad, in a way, but perhaps it was a blessing in disguise, for the ambitious youngster is said to have worked for some time at the local locksmith’s and learnt all there was to know about picking locks, an accomplishment that stood him in good stead later in life. Then came the turning-point of his career, for he obtained possession of a book dealing with the life of Robert Houdin, the great French magician. “This settles it,” cried young Weiss, as he closed the volume, “I’m going to be a professional entertainer!” Not long afterwards he achieved his object and started to tour with a friend named Hayman, the pair being known as the Houdini Brothers. It should be noted that Houdini’s name was an adaptation of that of the Frenchman whose book started him upon his long and successful career.

One must not assume that the way was easy, or that Houdini did not have to struggle. Like all successful men of magic, he had to carve his way to fame over difficult ground, and one hears of him appearing in a ‘dime museum’ at Chicago where he earned the princely sum of twelve dollars a week for some twenty shows a day. Even in those days he was a specialist, for the principal items of his programme were an escape from a specially prepared packingcase and a handcuff-release. Before he was twenty-one years of age this remarkable young man married a Miss Rahner, and after teaching his wife a little conjuring and some clever mind-reading, they both appeared on the music-hall stage as ‘The Great Houdinis.’

The man who had been Ehrich Weiss still had a long road to travel, and before achieving any permanent success he operated a Punch-and-Judy show, invented and made up card-tricks, and actually played the part of a wild man. One biographer of Houdini declares that he was shown to the crowds in a cage, growling and eating raw meat.

Years went by with their troubles and their triumphs, until at last an escape from handcuffs in a Chicago prison brought him the publicity he needed. I must at this point stress the fact that the magician, like all persons needing the constant support of the public, must have publicity—but I must also say that it has to be of the right kind! You cannot afford to lose an opportunity of getting your name before the public if you intend to be a public entertainer. Houdini was to prove a master of the art of ‘getting into the news.’

In 1900 we find the Houdinis in London, for the twenty-six-year-old magician had taken the plunge and spent all his savings on the trip across the Atlantic. At first he did not meet with much success, but when he showed the police-officials at Scotland Yard that handcuffs could not hold him, people began to awaken to the knowledge that in London was a person who had something new to show. “Who is this fellow?” they said. “Where can we see his show?”

Many engagements in London and on the Continent followed, and from that time Houdini never looked back. He had a few failures and minor disappointments, but they did not retard his upward march, and his triumphs soon followed one another in rapid and bewildering succession.

This astonishing man accepted challenges to free himself from fetters and to escape from prisons all over Europe and America. His fortune grew apace, yet for the sake of his art he never spared himself. Now we have seen that Houdini had grown into a specialist; yet he knew that his public would grow tired, and so he refused to rest content with one act as so many misguided magicians have done. ‘The Great Houdini’ was as proud as a peacock of that title, and he was determined that none should take it from him.

That is the brief history of Houdini, but I do not think we should leave him without mentioning some of his most extraordinary exploits. I must confess that I hardly know which to choose to show you just how clever this magician was, but before describing a few of Houdini’s tricks, I would like to make it perfectly clear that he was only a trickster. There was nothing supernatural about him—just a wonderful body with each muscle trained to obey his will, a clever brain to work out the details of some of his remarkable escapes, a knowledge of locks second to none, and an unending supply of patience which enabled him to practise and practise until there was not the slightest chance of failure.

Houdini was very proud of his escape from a large bank-safe and was wont to cite this as one of his finest triumphs. This being so, I think I cannot do better than describe it and label it as ‘Houdini’s Greatest Trick.’ The trick originated through the escapologist’s challenge to the safe-makers of London that he would escape publicly from any bank-safe in the City. His challenge was accepted by a well-known firm, and it was arranged that Houdini should make his escape from a new safe on the stage of the Euston Palace Music-hall in London. The only condition he made was that the safe should be delivered to him twenty four hours before the show.

Now comes an example of the genius of the man, and all those who aim at successful stage-careers as magicians should learn the lesson this story is intended to teach. In the first place Houdini made certain that all London knew of his daring undertaking. Secondly, he made a speech in which he stressed the danger of the performance, by hinting that a man could not breathe for long inside the safe. Thirdly, he insisted upon being medically examined on the stage. Fourthly, he kept his audience on tenderhooks for three-quarters of an hour when he could have escaped from the safe, so it is said, in a few minutes.

It was trickery all the way through—but how?

Houdini’s secrets have never been authentically disclosed, for like a true magician he refused to reveal his secrets. The story that has gained greatest credence is that during the time he had the safe at his disposal, he tampered with the mechanism of the lock by replacing the rather stiff new springs with springs of his own manufacture, and obtained the fake key necessary for opening the lock from the inside by shaking hands with a committee-man—picked from the audience!—after he had been thoroughly searched. A likely story, indeed, and one that many magicians, including myself, believe to be the most feasible. He escaped from the safe, according to this explanation, in a few minutes, but spent the rest of the time reading a novel behind the screen that was erected round the safe. That was real showmanship! Needless to say, he repaired the damage to the safe before it was returned to the makers, and emerged once more triumphant from his ordeal!

Perhaps the most baffling trick Houdini performed was that known as the ‘Box and Sack,’ and I am describing it to show you what ingenuity, quickness of movement, and showmanship can do for a magician. First of all, Houdini showed a strong wooden box and an ordinary sack on the stage, and while the audience watched carefully—as all audiences will—his woman partner was placed in the sack, which was tied tightly at the neck and lifted into the box. Then the lid was securely fastened, and a length of thick rope was tied around the box. After this the box was moved to the magician’s cabinet, some curtains were pulled in front of it, and Houdini made a spectacular dash into the cabinet from a distance of some yards. A moment or two later the curtain was pulled aside by one of the attendants to show that the man of magic had vanished, but the box was still to be seen, screwed and tied. At the same time as the curtain was pulled, the woman walked out free and strolled to the footlights amidst the thunderous applause of the audience.

What of Houdini? Where was he? In the sack in the box, of course, and as the audience realized that this box, screwed and roped, had certainly not been changed, they did not hesitate to acclaim the man who had baffled them with his mystifying trick. A secret panel skilfully concealed in the box made this clever illusion possible, so that it was the work of a split second for the woman to cut the bottom seam of the sack and crawl out of the box at the right moment, leaving Houdini to enter through the sliding panel and push himself up into the sack. It should be noted, however, as an example of the things audiences miss, that he was found in a sitting position when the lid of the box was untied. No one had the slightest suspicion that the bottom of the sack had been cut, because Houdini did not move from his position.

What was it that made the illusion such a success time and time again? It was the speed with which it was accomplished. I could cite case after case of speed making trickery look like sheer magic, and would-be illusionists of ‘big’ tricks should always endeavour to speed up their movements on the stage.

This great specialist in the magic art had an enormous repertoire of tricks and illusions, and among the others we find the ‘Needles and Thread’ trick, during the performance of which he was supposed to swallow needles and thread and then bring the former from his mouth all ready threaded; the ‘Vanishing Elephant’ illusion, which was the outcome of a chance remark that even he, the Great Houdini, could not cause an elephant to disappear; the escape from a milk-can filled with water, performed with the aid of false rivets and a double lining to the can; and the ‘Vanishing Horseman’ trick, which was so ingenious that I really must find room for its inclusion in detail in this chapter on specialists.

The illusionist rode on to the stage on a fine horse, dressed in a blue uniform and followed by a retinue of attendants in white. Two attendants produced a monster fan, which was held up so that the magician was concealed from the audience for a moment or two. These seconds behind the fan were very precious indeed, for Houdini tore off his blue uniform, which was made of paper, pushed it under the white uniform he wore beneath the blue one, jumped off his horse, and mingled with the attendants on the stage with very little fear of his being recognized—for the simple reason that no one bothered to count the attendants! Thus the complete disappearance of the magician when the fan was lowered was mystifying in the extreme.

For the rest of Houdini’s brilliant illusions, let me add that he startled the world by being buried in a coffin six feet under the ground and emerging none the worse for his ordeal after something like forty-five minutes. He dived into rivers and the sea well and truly chained and handcuffed, to appear on the surface of the water quite free a few seconds later. He hung suspended from a crane, manacled and roped as usual, and freed himself in a very short while although hundreds of feet in the air—a feat since imitated by other escapologists.

The feat of being buried alive was possible to achieve only because Houdini had taught himself how to conserve the oxygen in the coffin. He breathed very slowly and refused to lose his presence of mind. He often said, when speaking of this amazing feat, that if he did not remain perfectly calm while he was in the coffin, he would not live five minutes.

When we consider the case of another brilliant specialist, the ‘Chinese’ magician who toured the world under the name of Chung Ling Soo, we find an example of a man not only acting his part to perfection, but living it. Chung Ling Soo was no more a Chinaman than I am, his real name being William Elsworth Robinson, and his nationality Scottish-American. So well did he keep up this great illusion that only a very few people outside the profession knew of the deception until the tragic death of this clever showman-conjurer-magician. The manner of his death was astounding. He was shot dead by his assistant when performing his famous trick of catching bullets fired from a rifle on a plate held against his chest. Although he had performed this trick thousands of times with absolute success, a tiny hole in the barrel of the gun led to his ill-timed death on the stage of the Wood Green Empire, London, on March 23, 1918.

Chung Ling Soo, as we had better call him, performed against a perfect Chinese background and spoke in very broken English when announcing the tricks he was about to perform. Here was a case of a magician specializing to such an extent that he was almost alone in his particular sphere, and because of this he went from success to success. If it had once leaked out to the general public that he was not a Chinaman he would probably have been ruined. He kept his secret, however, because he almost came to believe that he was Chinese!

In order to explain his death I must give a few details of the ‘Catching the Bullets’ trick, which was the chief item in his programme. Two live bullets were passed to the audience and carefully marked before being carried back to the stage by a lady assistant, and apparently handed to a male assistant, who placed them in a rifle. Actually the real bullets were kept by the girl and handed to Chung Ling Soo at the same time as she handed him the plate. The bullets placed in the rifle were duplicates. Chung Ling Soo now took several steps across the stage and held the plate against his chest. The drums rolled. The assistant took careful aim with the rifle and pulled the trigger. At the same time there was a click, and the audience saw that the Chinaman had apparently caught the speeding bullet on the plate, although he had, of course, merely dropped one on to it as the rifle was fired.

The trick was made possible by having the barrel of the rifle divided down the centre, so that actually there were two tubes. Gunpowder was rammed into one, and the bullet was inserted in the other and held by a safety-clip. After the accident a tiny hole was found between the two tubes of the gun that had fired the fatal shot, and at the official inquiry that followed the death of Chung Ling Soo it was agreed that this small hole communicated the force of the explosion to the second tube and freed the bullet from its safety-clip. Death was a million-to-one chance, and the world of magic was poorer by the death of a very great magician who knew the value of showmanship.

This specialist served as a mechanic to several wellknown magicians and thus entered the world of magic by what may be termed the front door. He took to Chinese showmanship chiefly because he was a failure at patter and, after seeing the performance of a genuine Chinese magician named Chung Ling Foo, decided that he could better the performance. Because of the character of his act, too, he did away with the need for patter. Chung Ling Soo was one of the most painstaking of the masters of the art, and if he chanced to see an illusion that baffled him, he went to his workshop and experimented until he discovered the secret. I have always had the greatest respect for him and regarded him as something very near a genius. Among his other clever tricks were the ‘Oyster-shell,’ the ‘Growing Roses,’ and ‘Shooting through a Woman.’

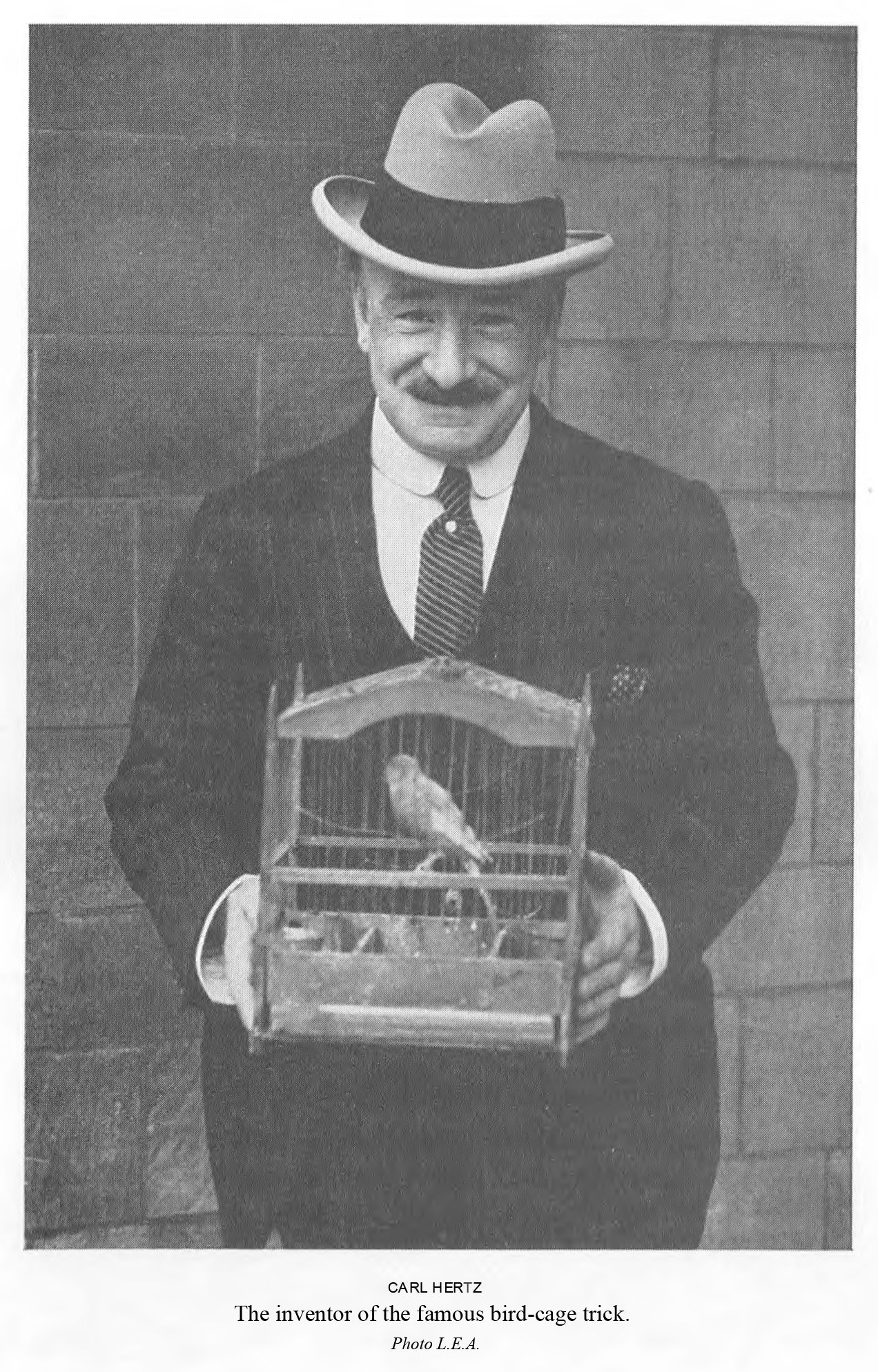

Not long ago I happened to be enjoying a ‘busman’s holiday’ at the Holborn Empire and saw a new and young magician perform the famous and baffling ‘Bird-cage’ trick. The audience applauded wildly, but I was silent because I was thinking of another great specialist named Carl Hertz, who specialized in making a square bird-cage disappear into thin air with the birds in it. Carl Hertz’s real name was Louis (or Leib) Morgenstein, and he was born in San Francisco, U.S.A., about the year 1869. He became a magician through sheer perseverance, and I have no hesitation in holding him up as a model to all young magicians who wish to succeed in the entertainment-world. After seeing a conjuring-performance by the Great Herrmann, he learnt a few tricks without any professional tuition, and practised so hard that he soon qualified to give stage-shows. At first he was not at all successful, and he actually blew a piece out of a man’s ear with a live bullet instead of a fake one during a revolver trick; but he did not despair and eventually became one of the leading lights in the profession.

His greatest triumph was when he successfully demonstrated, before a Select Committee at the House of Commons, that his bird-cage trick was not harmful to the birds. That demonstration really made Hertz, and thousands flocked to the halls where he was performing this bird-cage trick. One other story of this magician should be told. It deals with his appearance in Shanghai. He could not obtain a theatre, as the only one available was being used by a Chinese company performing a native play that would last for a week.

Carl Hertz immediately ordered a wooden theatre, and it was built for him in double-quick time by a Chinese builder on a piece of waste ground. The theatre cost no more than £10 to erect, because Hertz merely hired the wood used in its construction. The enterprising magician played to capacity for the whole month he was at Shanghai.

Lafayette’s specialization consisted of gorgeous scenery and curtains and soul-stirring music. His was the most spectacular act of all time, and, like poor Chung Ling Soo, his death was terrible and yet spectacular. He was burnt to death in the fire at the Empire Theatre, Edinburgh, on May 9, 1911, the desire for secrecy that caused him to keep the pass door from the stage to the stalls locked during his performance being the direct cause of his death. He made a dash for this door when the fire broke out, realized his mistake too late, and was overcome by the smoke and fumes before he could cross the stage again. The Great Lafayette was born at München, Germany, in 1872, and his real name was Siegmund Neuberger. Incidentally, I might mention the absolute necessity for a good stage-name should one’s own be unsuitable for the purpose. As we have seen, many of the great magicians, particularly the specialists, adopted names other than their own for stage-work.

It is very difficult for me to choose the best examples of specialists who have made a success of one particular branch of the magic art, but I do not think I can pass over Frank Van Hoven in this chapter. Although he has been dead some seven years, he is still known in the profession and by the public alike as ‘the man who made ice famous.’ His stock-in-trade as a burlesque magician was ice by the block, water, matches, and candles. He would talk incessantly in broken English, get small boys to hold blocks of ice, squirt water in all directions, and roam the theatre in a supposed search for a lady with white arms. “See,” he would cry, as he rolled up his sleeves, “nice white arms like a lady, nothing up my sleeve!” On and on would roll his patter, until the audience were reduced to tears of laughter and quite forgot that his tricks were of the simplest kind. There was nothing very mystifying about Frank Van Hoven, but he had a novel show that was sufficient to make him world-famous in a comparatively short time. He died at the early age of forty-two and was sincerely mourned by hundreds he had helped by his extreme generosity.

JASPER MASKELYNE

Before Magic Edition

PDF | 301 Pages

Jasper Maskelyne, the famous illusionist, presents a practical book that enables the curious to become expert entertainers in the art of magic. A guide filled magic effects you can perform with cards, coins, handkerchiefs, pieces of paper, rope and other common objects are described in detail. Chapters are also provided on stage management, thought-reading, disappearing tricks, apparatus, chemical tricks, entertaining in dress-clothes, jugglery and ventriloquism, and the art of make-up.

Coming from the famous Maskelyne family of magicians, Jasper also shares some excellent advice on rehearsing, structuring, writing, and booking a magical performance.

This magician proved that it is originality as well as speed, skill, and ingenuity that makes a man famous as a magician. He did not do at all well when he was a ‘straight’ magician, but he made up for lost time with a vengeance when he decided to model his performance on that of an English comedy-magician named William J. Hillier, who toured the United States so successfully at a time when Van Hoven was almost in despair at the failure of his act. Oddly enough, Van Hoven’s hobby was straight magic, and he amused himself for hours with the performance of ordinary illusions that he could not succeedwith in public.

Julius and Agnes Zancig were Danes, and it can be said that they had the greatest thought-reading act ever seen on any stage. Many people, including the late Lord Northcliffe, were convinced that they were possessed of psychic or supernatural powers; but the truth was that they were merely tricksters, like all other magicians, with a specialized act that made a fortune for them. In the beginning of his career Julius Zancig was engaged in iron-smelting, which shows that magicians can be made; but after several successes with his thought-reading act, he decided to abandon ironsmelting and embrace the professional stage. Agnes Zancig died some years before her husband, but Julius managed to find another gifted wife and partner in Ada Zancig and continued to perform with success until his death in America in 1929. The Zancigs had a code, but they employed many clever tricks in order to ‘read’ what was written inside sealed envelopes. On one occasion a reporter from one of the London newspapers approached Julius Zancig and declared him to be a fraud.

“I am firmly convinced that you are a fraud,” said this reporter, “but if your wife can tell me the word written on the card inside this sealed envelope, then I will believe in you and tell the story in my paper.” Zancig, the story goes, took the envelope, and although the newspaper man watched him closely, he did not see the magician press the envelope against a sponge under his armpit. Now comes the secret of something that amazed London at the time, for that sponge is said to have been soaked with alcohol, a spirit which makes paper transparent and leaves no smell, and of course Julius Zancig, it is alleged, had not the slightest difficulty in reading through the envelope and ‘ coding ’ the secret word to his wife to pronounce.

As for the secret code used by the Zancigs, it consisted in Julius framing his questions in a certain manner and thereby conveying to his wife exactly what kind of object had been handed to him. It needed long and continuous practice for these clever thought-readers to work their miracles, but I think I have shown you by this time that practice is the keynote of success in the profession.

There have been, and still are, many other great specialists besides those I have mentioned in this chapter, but I will not make you envious by mentioning any more. I will just leave it to you to decide whether or not to specialize in any particular branch of magic. You may do very well indeed as an escapologist, a card-manipulator, a Chinaman or Indian, a comedy-magician, or a thought-reader, but there is always the ever-present danger that the public will grow tired of your act. I am convinced that it is advisable for all young magicians to have a good repertoire of tricks, so that their work never becomes stale—so that to see them once or twice is not the end. A Chinese show one day, a ‘straight’ turn the next, and then a little escapology— is by far the best means of retaining confidence in your work.