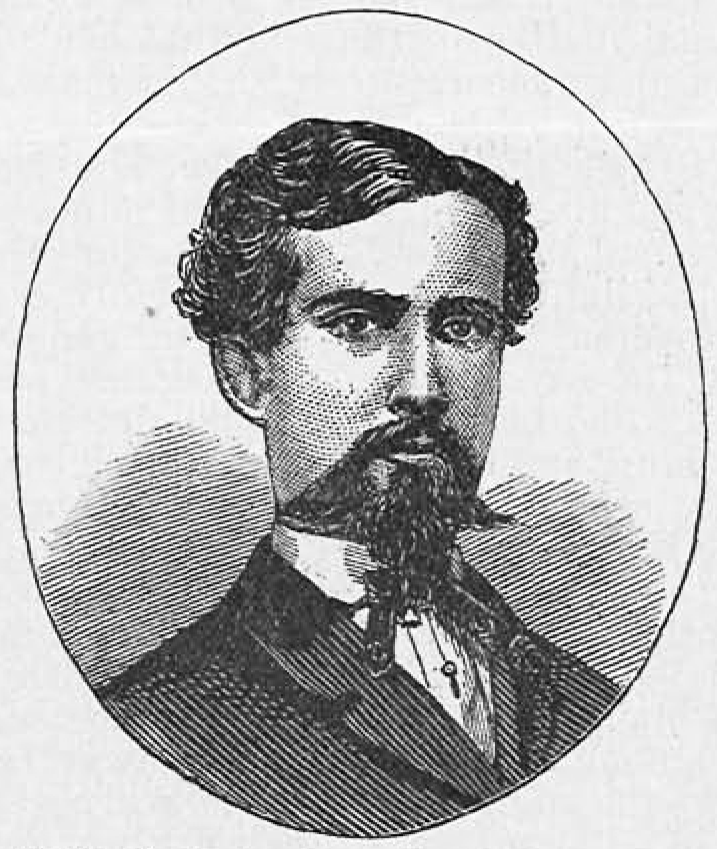

The Life and Five Years Before the Public, of ROBERT NICKLE, the World's Prestidigitateur

From the Houdini Library

After a number of years I have managed to trace Robert Nickle's birthplace, and only through a book published by the Centennial Magician himself. As far as I know this book from my collection is the only copy in existence. It was copyrighted in 1869, and only lately came into my possession. H. H.

My Dear Readers:

By this time most of you have heard of me and my wonderful doings, and would like to know who I am, what I am, and where I came from. Now, anxious reader, I will satisfy you upon this occasion, but briefly, hoping at some future period to be able to present to you a beautiful volume of my life and memoirs, which with my humble efforts, I hope to make one that will be long thought of and cherished by you. I was born on the second day of May, 1842, in the city of Troy, New York. My life, to the age of ten years, has no accounts of particular interest. At that age I commenced to learn the art of sleight of hand, and could always deceive my schoolmates. Like all boys at that age, I was very mischievous, in fact, more so than any of my mates, who looked up to me as a sort of leader; and with the master of the school I was always on good terms. I had a way, when I was late, to walk up to the desk and give him a nice, large apple, or a handful of fresh roasted peanuts, and with such a modest look that would cause him to smile, and sometimes the scholars; but he would silence them immediately. At times I would perform tricks in school, keeping the boys from learning their lessons, and very often-the girls, who had given me the name of Nick, being short for Nickle, and which only encouraged me the more, making me think there must be something in it, especially when one very pretty girl added the word young, making it Young Nick; and then at those times the expression of Old Nick was a very polite way to speak of the devil. As my tricks were never detected, insinuations were passed by the superstitious that I was controlled by an evil spirit. However, in less than two years I was the principal guest of all juvenile parties; and one would be held at any of the scholars' houses if they only thought I would come and perform my tricks. Being so flattered at the performance of my deceptions, I am sorry to say it kept me from learning any thing else; so that all the schooling I ever had was but two years—it might have been better for me if I had more. I cannot complain though at my present position and its consequences, as my goaheadativeness and quick learning at sight, has been a good deal the cause of my success.

In saying I was never detected, I must admit that upon one occasion I was, but all in thinking the schoolmaster was looking at me. I had a peculiar trick I called the moving mountain, or heaving of the quicksands. The floor of the schoolhouse was daily covered with nice white sand, which was always handy for me to do the trick with. The quantity I would use was about half a gill, placed in the palm of my hand, which at my command would commence to move and tumble about. The back of my hand, always resting on the desk, never moved, but yet the sand would; and so much so as to sometimes make people afraid I was wrong, as they would say. But that gave me the more confidence, and made me more expert. Even my mother would say, whenever I did anything great, "Robert, how do you do that? do tell me"; but O! no, I could not; for then she would have laughed, and said how simple, and all the neighbors would have known it.

I shall never forget when the moving mountain was discovered—there was not so much devil attached to my doings then, which remarks before always pleased me. The trick is of some interest on account of its simplicity; and as it was original I will describe it. Before commencing the moving mountain, I would have to catch unawares a large fly, concealing it between my second and third fingers of the left hand, and taking the sand from the floor with the right hand, I would put it quickly in the left over the place where the fly was hid; placing then the back of my hand on the desk, to show that my hand did not move, I would relax my fingers, and the fly not being able to go through the desk, and finding the sand above him forcible, would commence to work through it; and as I would naturally know when he was about to make his appearance on the top, I would put my other hand on the top, reversing the position of the sand—what was the top in the left, now became the bottom in the right, and so was the fly on the bottom, who now must once more work to the top. On seeing this, I had simply to change from hand to hand, as described, and the effect could be kept up as long as the fly moved. When it was discovered, some one remarked, "the master is looking," and the fly happened to be near the top at the time. In looking up to see if he was, and looking back to my hand, the fly was out; they all seeing it, exclaimed, "What a fraud!" Certainly it ended my trick of the moving mountain, as the whole school were the next day practicing it.

(To be Continued)

Originally published in the M-U-M in Vol. 8, No. 65 in New York, August 1918.

CONTINUED FROM AUGUST

Soon I had a new sensation, entitled "the invisible cockroach, or independent jack," when the "moving mountain" was forgotten, and they were trying to detect the other; but it never happened—as the first discovery was the last. It taught me a lesson, to be more on the lookout. I was always called a natural genius, and could do any thing I would see done if I wished to. The first magician I ever witnessed was old Professor McAllister, now dead, but whose tricks I detected, and was, in less than six months from the time, the possessor of two trunks of apparatus, which comprised twenty-five tricks. I was but thirteen years of age at the time, and my parents wished me to become a mechanic, engineer, or something of the kind, as they thought my talent ran that way, and it would be a more substantial business for me in the end; so I had to give in to it, and in two years I was running a locomotive. In my smartness to learn, I lost half an inch of my right thumb between the piston and connecting rods of the engine, while tapping the sandbar, which was clogged. This kept me idle for one year, when we moved to Canada. It was there I met with Professor Anderson, the Wizard of the North, whose favor I won in assisting his daughter Lizzy, who, at a carnival, had her arm broken by a clumsy fellow in the game of throwing a sledge-hammer. Seeing his performances, I added a great many new tricks to my repertoire, but had not yet the chance of following the art professionally, as I had long wished to. I had a great many opportunities to give parlor entertainments, and was guided by the criticism evinced on such occasions. I found, to become an artist, a great deal depended on being a good judge of human nature, and to suit the action to the word when performing an illusion or trick.

At eighteen years of age I was first tool-maker in a sewing machine establishment; having a great many opportunities to experiment, as my labor consisted in keeping the hands in the proper tools for their work, and, attimes, having a great many duplicates ahead, I would be at leisure to work for myself. In 1861 I visited New York, and witnessed the performances of the Great Herrmann — his style being so chaste and beautiful. I returned, and giving my apparatus a good course of renovation, it became the same as Herrmann's, ready to give his style of entertainment; but how was I to do it? I attempted before an audience of two hundred in number, and was pronounced perfect, and that there was no reason why I should not become as great as any of my predecessors. A great aid to it would be my never having had a master; and yet I was perfectly acquainted with the art; it seemed as if it was a second nature to me. In 1863 I gave my first public performance in a new hall on Front Street, Belleville, Canada, West, which was a success. My performances were then here and there until the third of July, 1865, when I opened with great success for one week at the Athenaeum, Brooklyn, New York. From there I visited the favorite watering place, Long Branch, New Jersey, where I was greeted with great enthusiasm, and then traveled through central New York.

On the first of January, 1866, I opened at Sam Sharpley's Opera House, Bowery, in the city of New York, now Tony Pastor's Opera House. I performed there four weeks, when I was engaged to go South and West, meeting with the favor of the press and public wherever I performed. On the 28th of January, 1867, I opened for one week at the Crosby Opera Music Hall, Chicago, Ill., and was greeted with large and fashionable audiences every evening. From there I traveled west as far as Omaha, astonishing all wherever I visited. In the month of January, 1868, I returned to Brooklyn, New York, performing at the new and spacious hall, the Institute, foil two weeks with full houses as a reward. On the sixth and seventh of March I opened for the- first time in Montreal, Canada East, at Mechanics' Hall, Great St. James Street, and was obliged to turn from the door four hundred people who were unable to gain admittance. The rush was the same on both evenings. From there I visited Belleville, Canada West, the place of my first performance, on the twelfth and thirteenth of March, where I was greeted by former associates, and proclaimed fully entitled to the title of "The World's Prestidigitateur"; which title, in connection with a new design streamer engraved with it on; also three life-size engravings in colors of original illusions, namely, the Nickle Money Feat, the Nickle Bird Cage Feat, and the Nickle Growth of Flowers, are entered according to Act of Congress as a protection from others copying the same. Other illusions, original, will be seen under the head of "The Most Pleasing is the Nickle Universal Brewery; The Most Surprising is the Nickle Globular Representations; The Most Astonishing is the Nickle Multum in Parvo; The Most Beautiful is the Nickle Marabout Mocha." These illusions, together with others, as only performed by the Great Herrmann and myself, comprise my Challenge Programme de Prestidigitation.

It has been, dear reader, my great aim not to do what other performers did, but to be original in all my representations. At present you find my programme mostly consists of original illusions. I promised to speak about my new invention, the act and play entitled "Satan in Paradise; or, Nature Outdone." It is an appearance of natural productions. Every one aware of the time necessary for all productions of nature, will observe in my proposed act and play that the idea to be conveyed is, what it takes nature years to accomplish, I will do in minutes. A perfect description of my act and play, given minutely, will not do here; as it is plainly seen there are so many imitators, who would vainly attempt to produce it, disgusting the public, thereby spoiling the effect of the original. Therefore, to protect myself from all infringements on the same, I have secured a copyright, which is in the words following, to wit:

The Act Play, Entitled "SATAN IN PARADISE"

or "NATURE OUTDONE"

Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1869 by Robert Nickle, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for Southern District of New York.

(Concluded next month)

Originally published in the M-U-M in Vol. 8, No. 66 in New York, September 1918.

CONTINUED FROM SEPTEMBER

The production of my act and play is of thirty minutes duration, closing with a beautiful and gorgeous Tableau of Nature. Also in it is pictured the title, "Satan in Paradise; or, Nature Outdone." A brief description of this wonderful representation will suffice for the present, hoping, sooner or later, to present it to a kind and generous public, as I have always found, in the country of my birth, America, and only to produce it in such style as to merit the patronage and ever, enthusiastic approbation of deserving talent, whether- at home or abroad. The curtain, on rising for the act and play, discovers an elegant and splendidly furnished parlor, formed to the shape of a box scene. The furniture is composed of six chairs, at the disposal of those in the audience who wish to take them. In the centre appears a light cabinet, the dimensions of which are six feet high, six feet in length, and three feet in width, with full open front, and doors to close. This cabinet rests on two ordinary trestles, three feet in height; on either side of the cabinet are two boards seven feet in length, and eighteen inches in width; these are also resting on trestles, three feet high; on both of the boards are six small chairs fastened, and with a strap to be hooked in front. The cabinet and stage then being examined, I proceed; going to the cabinet I close the doors; rappings are heard, and the doors fly open, discovering a large black shawl, on which is inscribed twelve beautiful roses of different colors, seen as the shawl is held up; giving then the remarks necessary for explanation, it is placed back in the cabinet, and the doors closed; the rappings commence; on the doors flying open again, the shawl has vanished; but instead appears a living babe, nine months old, dressed in a robe the color of one of the roses seen on the shawl. I take the babe from the cabinet; passing it in the audience it proves to be really as it appears, flesh and blood. It is then placed in one of the chairs arranged for the purpose, where it is quieted in the natural way—as my assistant, acting as nurse, gives it a stick of Wild's candy to keep it quiet. Then, in the same way, I produce the second, with a robe the color of one of the other roses. It is passed in the audience the same, then placed in a chair for the purpose. In this way I produce eleven living babes the age of nine months. I am about producing the twelfth to fill my last chair, when the doors flying open discovers the babe, but it is a black one, with Satan by its side. I approach the cabinet, taking the babe from it, and place it in the remaining chair, when Satan appears to want it back. Not wishing to spoil my tableau, or break the number twelve, he insists, however, on its return with gestures and insinuations, as much as to say, "You have not been satisfied to tamper with nature's productions for the earth, but wish to introduce my imps," and he demands a substitute, which I give in the person of my assistant. Satan, in receiving him, clutches him as a ferocious tiger, I close the doors on them. —the rappings commence—the doors fly open—they have both vanished; and there appears the large black shawl, but minus the twelve beautiful roses. In their stead is pictured, in the centre of the shawl, the horrible design of death—the skull and cross bones. The conclusion and proving of title is thus represented: for Paradise, I point to the cluster of pleasing and smiling babes; for Satan, as he just appeared, and being in the cabinet in the centre of the babes, I point to Satan in Paradise; then for Nature, I point to the babes, flesh and blood. Nature outdone is certainly the production of twelve at one time; thus the title, "Satan in Paradise; or, Nature Outdone." Showing then the sign of death, it is to him only the babes can now go; preferring to have him take his natural course, as with us all, I decline calling on him for their removal, as my act and play combines nature, the doings of nature, and through natural means.

Allow me thus, dear reader, to close my experience and doings as a Prestidigitateur; and as the art is nearing its end, look forward when the great feature of all amusements will be the Robert Nickle Act and Play, "Satan in Paradise; or Nature Outdone." Thanking you kindly forever to receive your generous patronage and encouraging applause,

I remain, yours truly,

ROBERT NICKLE.

Originally published in the M-U-M in Vol. 8, No. 68 in New York, November 1918.