Robert Heller's Brother Alive

Personal Recollections of His First American Appearance

By M.H. LEVETT

Copyright, 1919, by Harry Houdini

[Editor's Note.—Whether it is a case of eternal vigilance or pure luck, I am not quite prepared to say, but certain it is that I have had the rare good fortune to dig up some very interesting men and to secure from them facts that are of great value in rounding out the general history of Magic. To this list I now add the name of M. H. Levett, who acted as "subject" in Robert Heller's first introduction of second sight to an American audience, was advertised, and posed as Heller's brother.

Although he was very successful in the act, he was never really "Stage-struck," and after his engagement with Heller closed he turned to commercial pursuits.

Mr. Levett is a New Yorker by birth, having been born in Duane Street, on March 24th, 1837.

A most interesting relic of the Heller regime in the form of a second sight code in Heller's own handwriting has been presented to me by Mr. Levett.—Harry Houdini.]

Robert Heller, whose real name was William Henry Palmer, was an Englishman of noble birth, being the second son of a baronet. He first came to this country, as nearly as I can recollect, about the year 1851 or 1852. This was about the time that Jenny Lind and Laura Keene arrived; in fact, I believe that he arrived on the same ship with the latter.

Heller was a man of liberal education, of exceptionally refined manners; a linguist, speaking several languages, especially French; and a brilliant pianist, ranking with some of the best of his time, such as Rubinstein, Thalberg, and Strackosh.

In addition to this he possessed the rare faculty of infusing real comedy into his music, and after a brilliant rendition of some difficult composition he would introduce a comedy bit that never failed to convulse his audience. Among the best of these was an imitation of a young Miss practicing her music lesson—a whole long, weary hour taken right out of her life, when she might have been passing the time so happily with her little friends whose joyous laughter came floating through the window. The piece was that classic accessory of the old-time music teacher, "The Maiden's Prayer," and the rapid accomplishment of the easy passages, the slow and labored pounding out of the more difficult ones, and the frequent nerve-racking intrusion of false notes, was made excruciatingly funny. Every few minutes she had to stop to consult her watch and listen to see if it had stopped. Finally a brilliant thought struck her; she set her watch ahead half-an-hour and rushed off to her play.

Another was his pianologue depicting the experiences of himself and a friend one joyful night when they visited the opera and afterward made a tour of the booze palaces of Broadway. The comedy in this was a trifle less refined, perhaps, but it was a big hit always. He began with a potpourri from the then new opera of Faust, and described the two coming out saturated with the wonderful music and softly humming the melody of the catchy "Jewel Song"; and then, in the words of Heller, "My friend dropped into a bar to have a drink and I stayed outside—of another drink." They continued up the line, taking a drink in each gilded cafe, with the usual result. Quoting Heller again, "My friend actually drank seventeen pegs and I drank two (too)." With each new drink the rendition of the Jewel Song became more boisterous, but after a time the air became more uncertain and strange notes were interposed till finally it became apparent that these notes were from that inebrious classic, "We won't go home till morning." The intermingling of the two airs was very funny. Then the Jewel Song was slowly eliminated and the thing finished with "We won't go home till morning," sung by two sleepy voices in widely different minor keys.

ROBERT HELLER

From the Houdini Collection

I first became associated with him shortly after his arrival and continued with him for about four years. The nature of our work was such that we naturally became very intimate, which gave me the opportunity of thoroughly acquainting myself with his characteristics, and I may say that I knew him better than most of his friends and acquaintances, as I was guardian of his most cherished secret, that of his most important act—The Second Sight Mystery.

At the beginning of my engagement he was living in a private house in Grand Street, west of Broadway; having a workshop adjoining his suite, in which he made repairs, practiced, and held rehearsals in preparation for his opening at the Chinese Assembly Rooms, in Broadway between Spring and Prince streets; the building that was afterwards occupied by P. T. Barnum after his fire at Broadway and Ann Street. The building was fitted up especially for us, and we remained there about a year, the business proving satisfactory throughout.

During this engagement Heller assumed the disguise of a Frenchman—dark wig, eyebrows and moustache. His opening address was in French and the remainder of his patter in broken English, and he continued in this character throughout the entire year.

After closing in New York we went on tour, making the first stand in Albany, then to Boston, Portland, Syracuse, and several smaller cities.

It had always been a question whether the French disguise was an asset or a liability, and on leaving New York Heller decided that nothing was gained by it, either artistically or financially, therefore he abandoned it, and for the remainder of his career he appeared in his natural character; his blond—almost red—hair and moustache giving him a very different, and, to my mind, a much improved appearance.

In those days we used the "boy table"; that is to say, a table with a deep drapery which concealed a boy-assistant who worked the traps, automata, etc., but later the lever worked from beneath the stage was substituted.

The stage fittings were most luxurious. The set represented a drawing-room with Brussels carpet on the floor, the side-walls and back hung with maroon damask, and the centre entrance draped with yellow curtains over which fine laces were tastefully arranged, and above all a heavy gilt cornice.

A large table with hangings of festooned black velvet, edged with heavy gold bullion fringe, stood at centre; small tables at each side of entrance at back and on each side of the stage were similarly draped. Handsome sconces holding four wax candles each adorned the walls at sides and back, and all the tables were supplied with ornate candelabra. The entire battery of candles being lighted when the front drop was drawn aside, the scene presented was like a palace of enchantment.

No apparatus of any kind was visible on the stage, nor were there any confederates in the audience, both of these being departures from the usual custom of that day.

The tricks presented were largely mechanical, such as The Orange Tree, The Mill, etc., but Heller introduced some sleight-of-hand work which was of the highest order.

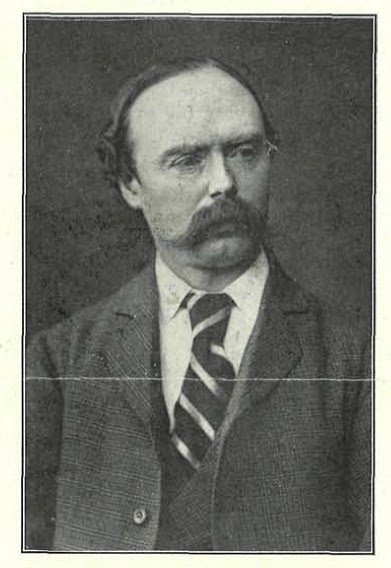

M. H. LEVETT

From the Houdini Collection

The second part was entirely musical, introducing the features mentioned above, and the third was devoted to the Second Sight Mystery, which was the most important feature of his program, and proved a most fascinating puzzle to press and public. We would change our method frequently, so that when some of the regular attendants thought they had the secret, some slight change would upset their theory completely. Of course, there were those who thought that I really possessed some kind of superhuman power, but Heller never encouraged such beliefs.

In the silent method he sometimes used a small table bell, apparently to attract the attention of the medium. This bell had no significance, and was merely used to deepen the mystery. In this method only large articles were used, and they were held up so as to be seen by the lookout through the peep hole and communicated to the medium through the speaking-tube.

Electricity was never used in this act during my time. There were no dry batteries in those days, but we used a cell battery for working the rappings, the crystal cash box, and one or two other tricks. What Heller did after I left him I do not know. I saw many of his performances in later years, and I know that the Second Sight was worked by a code quite different from the original, but I could follow him fairly well after giving a little attention to his new methods.

There was a time—I cannot recall whether it occurred during our first year in New York, or on our return a year or two later—when Anderson and M'Allister were both playing at the same time we were; M'Allister at Mechanics Hall, on Broadway above Grand Street—the Christy Minstrels were there later—and Anderson at a hall further up Broadway. The latter advertised that he would make an expose of our Second Sight on a certain evening, but when the time came he ignored the subject entirely.

During the Boston engagement he put "Mrs. Heller" on in the Second Sight as an added attraction; she was a very handsome woman, but in the act she was only a mouthpiece, as I took all the cues and prompted her from the wings through a speaking-tube which ran up through a sort of piano-stool oh which she sat. Her work was not satisfactory, and he took her off after a few weeks' trial. Haidee, his alleged sister, I did not know. I witnessed her work with Heller, but I have no comment to make.

After we separated he picked up a young man in Cincinnati, Ohio, a son of wealthy parents, who put some money into the show. This man worked in the Second Sight for some time, but dropped out for some reason unknown to me, and shortly after exposed the entire code in one of the Cincinnati newspapers. I heard of this about a year later, but was unable to get a copy of the paper. This was before the advent of Dale or Haidee.

It was some little time after this that Heller was reported dead, and I supposed such to be the case until I accidentally met him in New York, very much alive, being dead only to his creditors. He told me that he had been with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra as a pianist, at $200.00 per week. Not long after he started in the old line again, I think with Haidee.

I next saw him at the Fifth Avenue Theatre, at 24th Street, which had been newly fitted up for him, and I did not see him again until his last engagement in New York, which was at the old church building opposite Lafayette Place on Broadway, where, he said, he made some money. From there he went to Philadelphia, where he died, November 28th, 1878.

To go back a little, on our return to New York after our first tour we opened at a hall on Broadway opposite Bond street, where we did a fairly good business. The San Francisco Minstrels, with Billy Birch, Dave Wombold, Bachus and others occuppied this hall later.

In those early days showmen had to take their own risks; hire a hall or theatre, bill the town, advertise, and meet all other expenses: taking the profits—if any. There were no such things as contracts with owners or managers except in the case of dramatic stars.

After our engagement in Portland, Maine, we laid off in that pleasant neighborhood during the heated months, Heller making frequent visits to Boston. On one occasion he received an invitation to give an entertainment in the hotel at Cape Elizabeth, about three miles from Portland, and we gave a sort of musicale: no tricks other than second sight, the remainder of the program being vocal and instrumental music. A somewhat humorous incident followed. After the performance a merry crowd got together and when the party broke up at near 4 a. m. it was decided that Hellar and I should drive back to town in a couple of buggies that were to be returned to a livery stable. We had covered perhaps a mile of the lonely road when Hellar's buggy struck an obstruction, a mile-stone, I think, and overturned, breaking one of the shafts and a few spokes, and putting the outfit completely out of commission.

The horse fortunately did not run away—he was warranted to stand without hitching—but he lost his "spirits." We held ours! However, we bound up our wounds as best we could and resumed our journey. Hellar, being bruised and somewhat absent minded, got into the good buggy, and I took the other horse by the bridle and led the shattered outfit all the way back to town.

The joke was certainly on me. Why did I not tie the "sick horse" behind the good buggy and ride into town with Hellar? Echo answers, "Why?" Damage—$40.00 and a few scratches.

Sir William Henry Palmer came into his title about the year 1876. The writer met him in New York about that time. He was not playing, and I distinctly remember his words to me on that occasion: "Well, I came into the title, but damn the title! I wanted money." From which I inferred that it was a barren title merely.

Of his family affairs I heard some little, but it would be out of place to speak of them here, except to say that he married a Miss Riggs, of Washington, D. C.

Heller was an all round good fellow; very magnetic; fascinating and witty in conversation, and he could have earned a good living either as a musician or an actor on the legitimate stage, and, in closing, I can truly say, in the words of Hamlet: "He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his Iike again."

Originally published in the M-U-M in Vol. 8, No. 74 in New York, May 1919.